The rise of open banking globally over the last few years has led to the adoption of Financial Grade API (FAPI) built on oAuth2, as the standard of choice for authentication and authorization. But this approach could leave billions of people disenfranchised from the greatest financial innovation over the last decade.

Open banking makes financial services intuitive and customer-friendly because it creates a single language for banks, fintechs, and other stakeholders to speak. By creating open banking, various jurisdictions are paving the road for the greatest growth in financial services.

FAPI and OAuth2 are both security protocols that are used to authenticate users and grant access to protected resources. The main difference between the two is that FAPI is an extension of OAuth2 that provides additional security measures specifically designed for use with financial services. FAPI uses stronger authentication methods and encrypted communication channels to protect sensitive financial data, whereas OAuth2 is a more general-purpose protocol that can be used in a variety of different contexts. In general, FAPI is considered to be more secure than OAuth2, but it may also be more complex to implement.

FAPI, a more secure version of OAuth2, is often preferred for authenticating users and obtaining their consent. This is because OAuth2, which was developed by the OpenID Foundation, has already become a widely-used global standard for authentication and authorization. It is used by many of the largest internet services, such as Google and Facebook, and is accessed by billions of people every day. Due to its proven track record and strong security measures, FAPI is seen as a reliable and effective solution for protecting sensitive financial data.

Global open banking initiatives adopt FAPI

With the launch of open banking in the UK, the Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE) adopted FAPI, which goes the extra mile to fortify oAuth2 as open banking would be the rails on which trillions of dollars would move each year for millions of British account holders.

The success of the British open banking regime has led to a global acceptance of FAPI for authentication and authorization. It makes sense – if it works for the global leader in open banking, why do something else?

Banking isn’t uniform across the globe.

In all developed countries, most account holders use smartphones or desktop browsers to access their banking services. This is where FAPI wins, and it is taken for granted – after all, FAPI was built for secure financial services on the internet.

However, banking services run over USSD, SMS, and other dump channels in Africa and developing countries. And the percentage of these users is not trivial. For example, over 35 percent of Nigerian account holders use USSD to transact. That is just for those that are financially included. Almost 50% of Nigerians are financially excuded, mostly the poor at the bottom of the pyramid without access to smartphones and the internet.

The government, the Central Bank of Nigeria, and other stakeholders are working strenuously to bring them to financial services.

This story plays out in every African country.

What this means is that if Nigeria and other countries were to adopt FAPI wholesale for open banking, these billions of people would be unable to participate. FAPI could then perpetuate the same problem of financial exclusion.

So what’s the solution?

The goals of FAPI are clear and cannot be compromised – secure financial services underpinned by strong security and clear consent. The goals of financial inclusion can also not be compromised as well.

The team at Open Banking, having engaged the OpenID team for months, initially felt that FAPI may be the best way to go and leave the adoption for the excluded to another time, another decade?

But because of our strong objectives for financial inclusion, built into the Nigerian open banking ethics, we developed a draft implementation where the tenets of FAPI can be respected while allowing secure services over dumb channels.

How does FAPI even work?

FAPI is hardened oAuth2. oAuth2 is a technology standard that allows an end-user to grant access to resources of the end-user securely without exposing the user’s credentials. It also allows the user to specify the roles or permissions the service-granted services could have. For some sophisticated systems, the timing can even be specified. The user can also revoke access without changing their username and password.

oAuth2 has been extensively documented here for those who need to dive in deeper.

Without FAPI, many users using services like Plaid in the US or Mono in Nigeria have to give their most secret credentials to these services to do what they think is open banking. While these services are respectable and innovative, the reality is that this is a very dangerous practice that should be discouraged as a single sophisticated hack could potentially destroy the livelihood of millions of people.

How would this work?

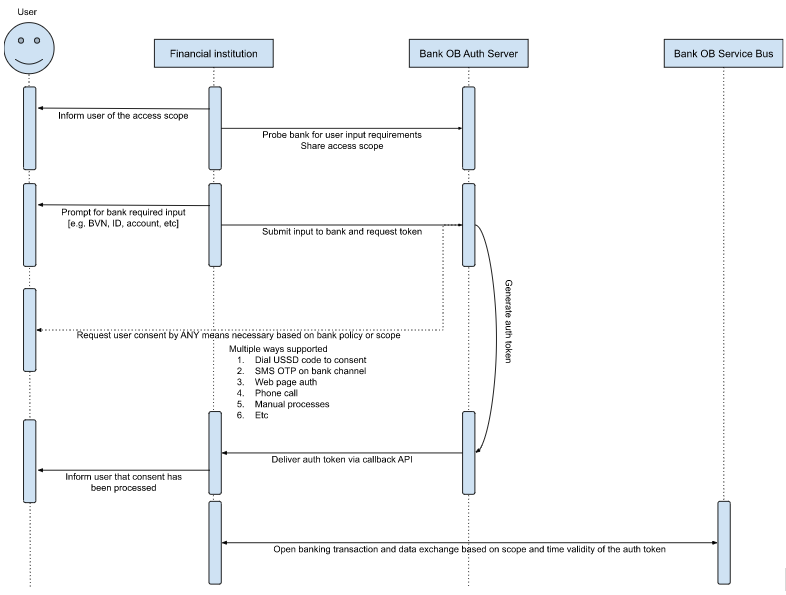

We have designed a process with the following actors:

- Dumb channel: Any channel that cannot carry internet traffic natively (or sometimes, in an enhanced form). This includes SMS, USSD, POS, ATM, and bank branches.

- End-user: The customer who wants to use a dumb channel to access services from a Service Provider

- Client: The service provider who wants to offer financial services to an End-user over a dumb channel. Within the Nigerian open banking context, this is called an API Consumer (AC)

- Financial institution: The bank or fintech with which the End-user has an account but with which the Client wants to access.

Using the process flow depicted in the System flow diagram below, an End-user engages with the Client, for example, to be able to debit their accounts regularly for loan repayment.

The Client collects identifying information from the End-user through the dumb channel and forwards it to the Financial Institution over a secure Open banking channel. The identifying information would be a low-security identifier. For example, their bank account.

The Financial Institution would then send an authentication and consent information to the End-user on a separate channel (usually another dumb channel) for the user to authenticate themselves. This authentication may include some one-time use code.

Once the End-user has done this, the Financial Institution sends a token to the Client and then the Client informs the End-user (over a dumb channel) that the consent has been processed.

Acceptance Criteria: The choice of dumb channel for the financial institutions to engage with the End-user should be limited to SMS and push USSD.

Risk mitigations; ensuring security for the End-users

Access to customer data over dumb channels would always be fraught with risks, but with careful considerations, mitigants and guard rails could be implemented to limit the possibility of risks. Furthermore, these risks can be owned by the parties that are sophisticated enough to understand and also manage them.

The following are the mitigation approaches proposed by Open Banking Nigeria:

The scope and limits of the consent granted by an End-User to a Client MUST ALWAYS be limited – for example, limits can be on amounts, length of time for access, etc.

The open banking regime MUST SPECIFY a higher and more stringent security standard for the Client than a typical open-banking client.

The number of connections for a Client for End-users over dumb channels may be capped to prevent abuse.

And most importantly, there would be a 100% liability shift from the End-user and the Financial institution to the Client.